C3: cloth culture community - exploring 1,000 of Black Pittsburgh through clothing

artist-in-residence Contemporary Craft

C3: Cloth, Culture, Community

Exploring 1,000 years of Black Pittsburgh through clothing

C3 began with the question, “Who was the first Black person in Pittsburgh?”

The answer led to an exploration of over 1,000 years of history, beginning in West Africa and taking us all the way to the year 3000. From African queens to war veterans, and coal miners to civil rights activists.

Designer and writer, Tereneh Idia, shares a dozen stories that shed a light on our all too often overlooked but powerful ancestors who helped shape the Pittsburgh region, America, and the world.

Studio photos by Njaimeh Njie

exhibition photos by Tereneh Idia

Exploring 1,000 years of Black Pittsburgh through clothing

C3 began with the question, “Who was the first Black person in Pittsburgh?”

The answer led to an exploration of over 1,000 years of history, beginning in West Africa and taking us all the way to the year 3000. From African queens to war veterans, and coal miners to civil rights activists.

Designer and writer, Tereneh Idia, shares a dozen stories that shed a light on our all too often overlooked but powerful ancestors who helped shape the Pittsburgh region, America, and the world.

Studio photos by Njaimeh Njie

exhibition photos by Tereneh Idia

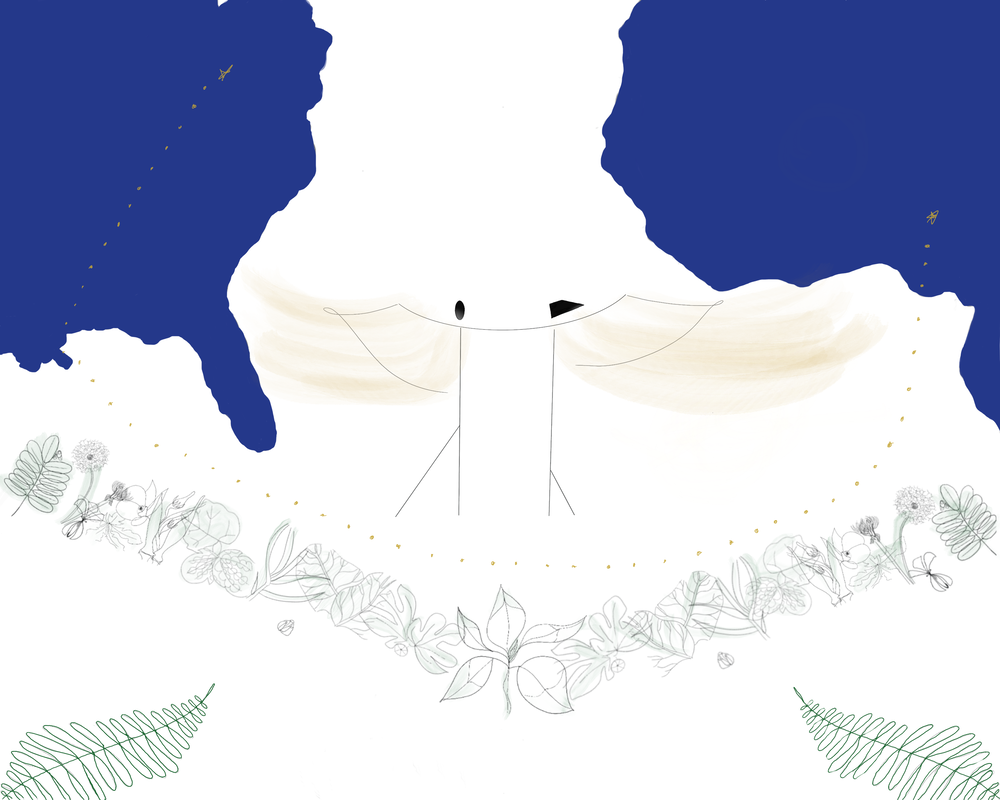

C3 Flag

in honor of Black Pittsburgh

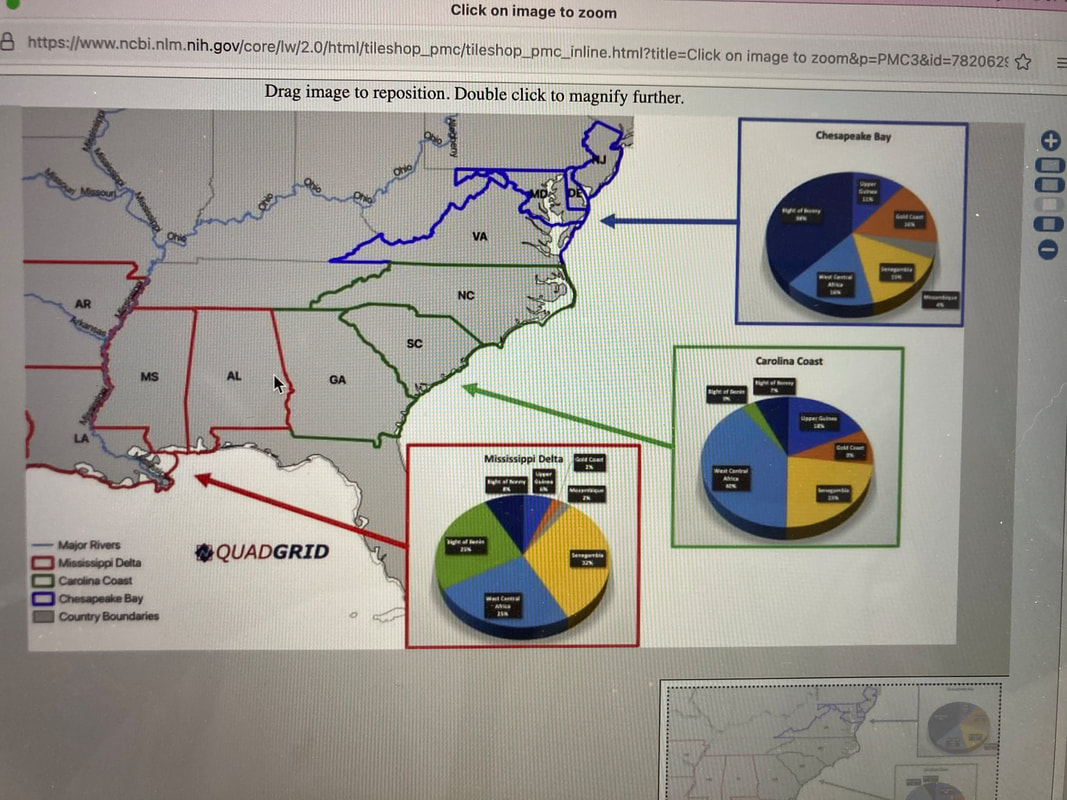

This image shows a portion of the East and Gulf Coasts of the United States with a portion of the coast of West Africa. The dotted line tracks the route across the Middle Passage to Louisiana and up through to Pittsburgh, PA.

Yes, Africans were enslaved in Pittsburgh. Yes, there were free Africans in Pittsburgh.

The flag is framed by important foods and natural medicines found in West Africa, the southern United States, and in Pennsylvania including Lagos spinach, collard greens, pumpkin leaf, okra, dandelion, garlic, and wild senna. These are flanked by ferns, which were used by escaped enslaved Africans as a guide to find fresh water.

At the center of the flag is a symbol of the Flying African and Eagle as one entity. The Flying African, is a symbol of the desire for those in the African diaspora in the Americas to seek freedom through our gifts. The eagle is the national symbol for the United States; it is also on the Nigerian flag coat of arms, as a symbol of Nigerian independence from British colonialism. However the Ugo is the Nigerian eagle, and has much older significance as an animal of honor and reverence which can be seen in traditional masquerade ceremonies.

Throughout the exhibition you will see garments made from this fabric as well as elements of the flag appearing in many of the outfits.

Credits

Design and Drawing: Tereneh Idia

Printing: Artists Image Resource (AIR)

Ink mixing and Design: Rachel Rearick

References

Lucretia VanDyke. (2022). African American Herbalism: a practical guide to healing plants and folks traditions Ulysses Press.Michelle E Lee. (2014). Working The Roots Over 400 Years of Traditional African American Healing.Wadastick Publishers.

M.G. MOKGOBI. (2014). Understanding traditional African healing. National Institute of Health.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4651463/.

Angela Rahim. (2020). Sam the Junior Herbalist book series. https://www.samthejrherbalist.com/

Oasis Farm and Fishery Pittsburgh. https://www.oasisfarmandfishery.org/

in honor of Black Pittsburgh

This image shows a portion of the East and Gulf Coasts of the United States with a portion of the coast of West Africa. The dotted line tracks the route across the Middle Passage to Louisiana and up through to Pittsburgh, PA.

Yes, Africans were enslaved in Pittsburgh. Yes, there were free Africans in Pittsburgh.

The flag is framed by important foods and natural medicines found in West Africa, the southern United States, and in Pennsylvania including Lagos spinach, collard greens, pumpkin leaf, okra, dandelion, garlic, and wild senna. These are flanked by ferns, which were used by escaped enslaved Africans as a guide to find fresh water.

At the center of the flag is a symbol of the Flying African and Eagle as one entity. The Flying African, is a symbol of the desire for those in the African diaspora in the Americas to seek freedom through our gifts. The eagle is the national symbol for the United States; it is also on the Nigerian flag coat of arms, as a symbol of Nigerian independence from British colonialism. However the Ugo is the Nigerian eagle, and has much older significance as an animal of honor and reverence which can be seen in traditional masquerade ceremonies.

Throughout the exhibition you will see garments made from this fabric as well as elements of the flag appearing in many of the outfits.

Credits

Design and Drawing: Tereneh Idia

Printing: Artists Image Resource (AIR)

Ink mixing and Design: Rachel Rearick

References

Lucretia VanDyke. (2022). African American Herbalism: a practical guide to healing plants and folks traditions Ulysses Press.Michelle E Lee. (2014). Working The Roots Over 400 Years of Traditional African American Healing.Wadastick Publishers.

M.G. MOKGOBI. (2014). Understanding traditional African healing. National Institute of Health.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4651463/.

Angela Rahim. (2020). Sam the Junior Herbalist book series. https://www.samthejrherbalist.com/

Oasis Farm and Fishery Pittsburgh. https://www.oasisfarmandfishery.org/

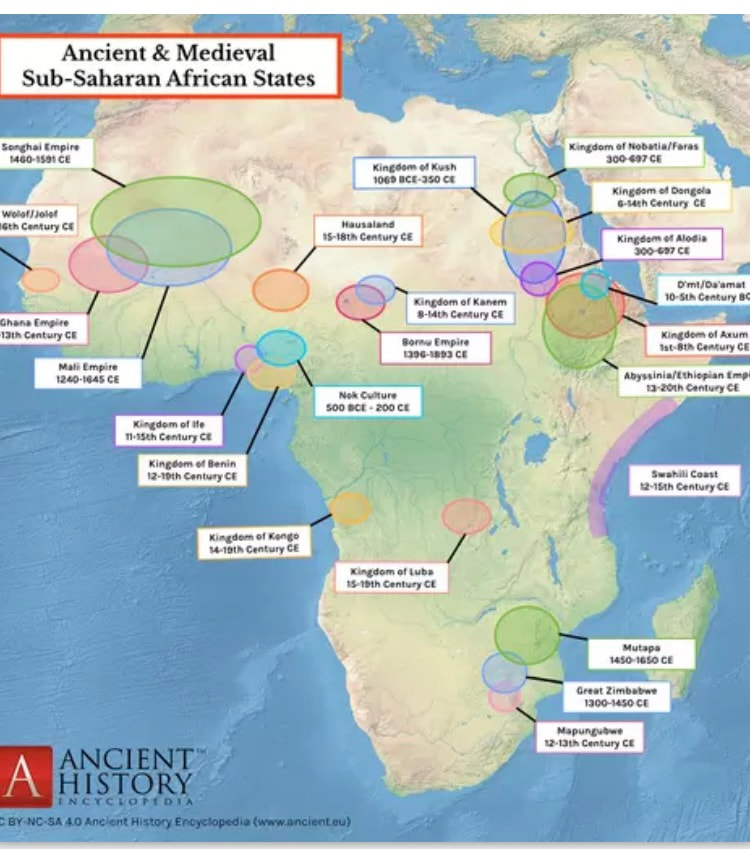

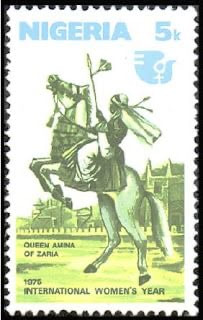

Queen Amina circa 1500s

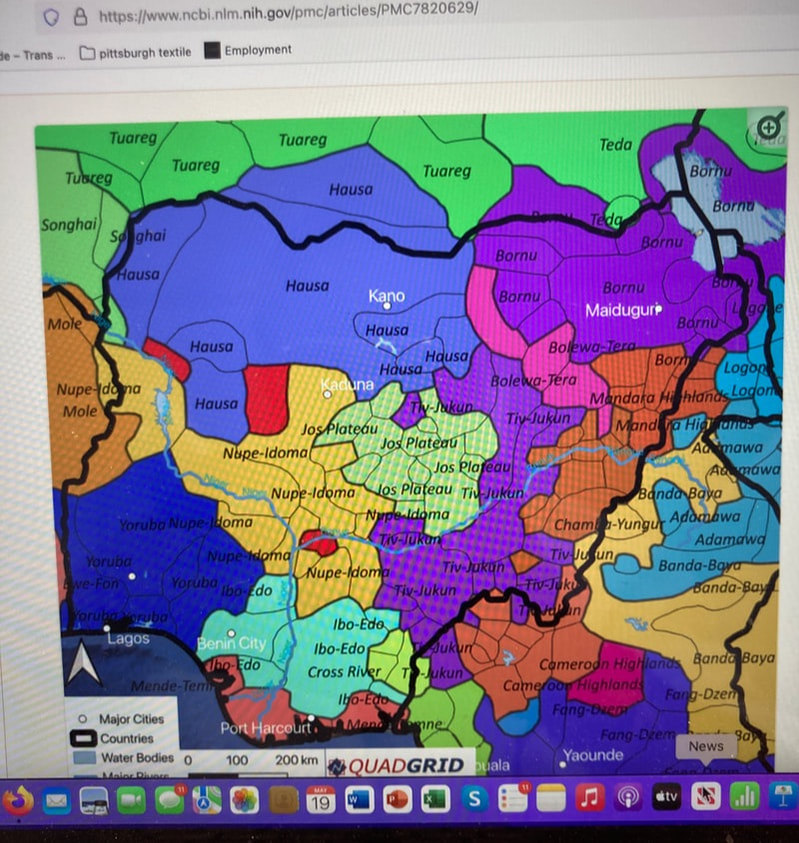

We begin C3 in West Africa, specifically Hausaland which is now modern day Nigeria. In the state of Zazzau, Aminata, also called Amina, was born in 1533. Some date her life back to the 1400s, while others deny her very existence. However, the Nigerian stamps and statues featuring Queen Amina’s likeness points to someone who was a very real Queen.

When her father died in 1566, her younger brother Karama was named ruler which was not a surprise in this Islamic state. What may be a surprise was that Amina loved anything military. Armor, swordplay, equestrian skills - Amina was in her element.

After the death of her brother in 1576, Amina became the Queen and ruler of Zazzau. Given her lifelong interest in and commitment to all things related to battle, she quickly gained respect and developed a close bond with the military. In fact, it was said that Amina was so committed to armorsmithing that she introduced chainmaille working to the Zazzau army.

While Amina refused to marry, instead focusing on increasing the wealth and strength of her community, which she achieved, she would take temporary husbands after battle. The legend goes on further to say that she would kill these men the next day. To learn more about Queen Amina, please see the resources below.

Outfit: Queen Amina

Chainmail breastplate, 18 gauge aluminum chain links

Tunic, hemp and organic cotton silk

Equestrian culottes, upcycled upholstery fabric from Center for Creative Reuse

T-shirt, soy jersey t-shirt

Crown, recycled brass, designed and created for the C3 project by Selima Dawson of Blakbird Jewelry

Artist Reflections

As an undergrad at Drexel University, I donned a pair of wide trousers and a head wrap. In the middle of the Main Building I yelled “I am Amina of Zazzau, Hausaland!” It was for Black History Month. At the time I was the head of the Black Student Union and it was my idea to “Make Black History come alive” by having people dress up as historical figures. I cannot remember if I was the only one who showed up to do this but I remember yelling out “I am Amina!”

I first learned about her because of the beautiful and heroic image of her on a Nigerian stamp. I was enthralled and still am.

Resources

African Feminist Forum. http://www.africanfeministforum.com/queen-amina-of-zaria-nigeria/

Queen Aminatu Mohamud. Africans for Africa. https://www.afa-afa.org/african-queens/queen-amina

Queen Amina: Nigerian warrior queen. BBC. https://www.bbc.com/news/av/world-africa-44888718

Amina of Zaria: The Warrior Queen. https://www.darabeevas.com/new-products/amina-of-zaria-the-warrior-queen-book-1-of-lil-queens-series

We begin C3 in West Africa, specifically Hausaland which is now modern day Nigeria. In the state of Zazzau, Aminata, also called Amina, was born in 1533. Some date her life back to the 1400s, while others deny her very existence. However, the Nigerian stamps and statues featuring Queen Amina’s likeness points to someone who was a very real Queen.

When her father died in 1566, her younger brother Karama was named ruler which was not a surprise in this Islamic state. What may be a surprise was that Amina loved anything military. Armor, swordplay, equestrian skills - Amina was in her element.

After the death of her brother in 1576, Amina became the Queen and ruler of Zazzau. Given her lifelong interest in and commitment to all things related to battle, she quickly gained respect and developed a close bond with the military. In fact, it was said that Amina was so committed to armorsmithing that she introduced chainmaille working to the Zazzau army.

While Amina refused to marry, instead focusing on increasing the wealth and strength of her community, which she achieved, she would take temporary husbands after battle. The legend goes on further to say that she would kill these men the next day. To learn more about Queen Amina, please see the resources below.

Outfit: Queen Amina

Chainmail breastplate, 18 gauge aluminum chain links

Tunic, hemp and organic cotton silk

Equestrian culottes, upcycled upholstery fabric from Center for Creative Reuse

T-shirt, soy jersey t-shirt

Crown, recycled brass, designed and created for the C3 project by Selima Dawson of Blakbird Jewelry

Artist Reflections

As an undergrad at Drexel University, I donned a pair of wide trousers and a head wrap. In the middle of the Main Building I yelled “I am Amina of Zazzau, Hausaland!” It was for Black History Month. At the time I was the head of the Black Student Union and it was my idea to “Make Black History come alive” by having people dress up as historical figures. I cannot remember if I was the only one who showed up to do this but I remember yelling out “I am Amina!”

I first learned about her because of the beautiful and heroic image of her on a Nigerian stamp. I was enthralled and still am.

Resources

African Feminist Forum. http://www.africanfeministforum.com/queen-amina-of-zaria-nigeria/

Queen Aminatu Mohamud. Africans for Africa. https://www.afa-afa.org/african-queens/queen-amina

Queen Amina: Nigerian warrior queen. BBC. https://www.bbc.com/news/av/world-africa-44888718

Amina of Zaria: The Warrior Queen. https://www.darabeevas.com/new-products/amina-of-zaria-the-warrior-queen-book-1-of-lil-queens-series

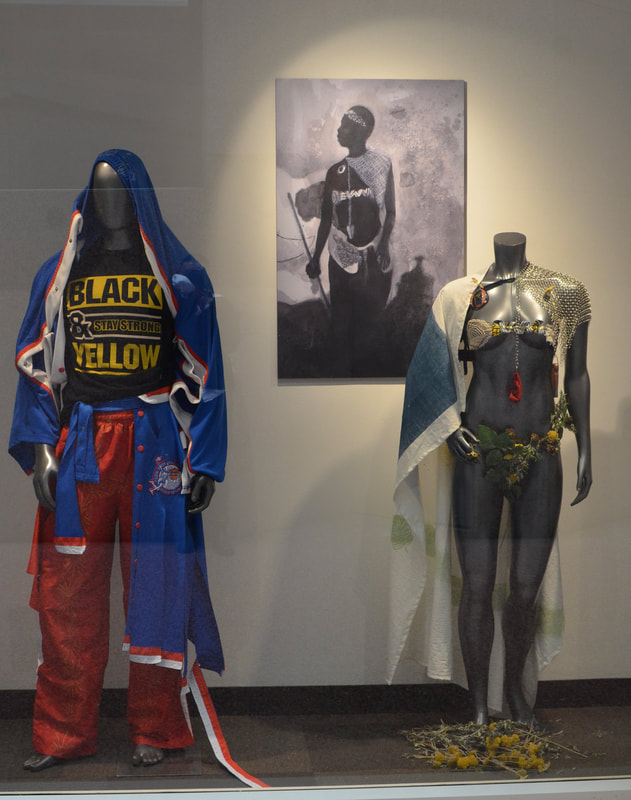

Flying African

“Have you ever heard of Flying Africans?” I asked a friend of mine who lives in St. Vincent and the Grenadines.

“Oh yes, you mean the Africans that flew away from enslavement?”

Bessie Coleman, the famous African American woman pilot, spoke of the freedom of flight. Some in the Oneida Indian Nation say the Black people were given providence and responsibility over the air. One traditional Maasai folk tale says that they originated when Narok, their black deity, extended their arms down from the cosmos, leading the Maasai down to earth.

Some believe Black people can fly.

The most famous American-based story of Flying Africans can be heard in the seminal film by Julie Dash, Daughters of the Dust. We learn of Igbo Landing in Georgia, a place where hundreds of years ago a group of 18 Igbo from Nigeria came to these shores in a slave ship. Once they left the ship and saw their fate, the slave auction block, they joined hands. Instead of walking together to the slave market they walked back to the water. Some say they drowned, others say they flew back to Africa.

“I’ll Fly Away”

“All God’s Chillun Had Wings”

In 2022 a new series of murals in Philadelphia are being created by Brooklyn-based artist Tatyana Fazlalizadeh, called Flight. The first one was unveiled in October 2022. https://paulcoletravels.com/2022/11/07/magical-mural-with-a-message-takes-flight-in-philadelphia/

Outfit: Flying African

Dress: hemp and organic cotton silk with water-based ink block print pressed through the lace of the wings.

Wings: upcycled lace from Center for Creative Reuse

Artist Reflections

One of the internal and external questions that most African Americans I know have asked is, “What would I have done if I was enslaved?” I often say I do not think I would have survived very long. The 1991 film Daughters of the Dust taught me the Igbo Landing story. The eighteen Igbo who, it was told, joined hands and walked back into or over the water to freedom has always resonated with me.

Upon learning that slave revolts were more likely to happen when more women were on board slave ships did not surprise me. This garment was created in honor of all of the Africans who transitioned along the Middle Passage.

Research

McDaniel, L. (1990). THE FLYING AFRICANS: EXTENT AND STRENGTH OF THE MYTH IN THE AMERICAS. Nieuwe West-Indische Gids / New West Indian Guide, 64(1/2), 28–40. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24027305

https://www.newyorker.com/culture/culture-desk/revisiting-the-legend-of-flying-africans

Barnes, P. C., & Barnes, P. (2009). Pearl Cleage’s “Flyin’ West” and the African American Motif of Flight. Obsidian, 10(1), 68–82. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44473575

HALLOCK, T. (2019). Space, Time, and Purpose in Early American Texts: Starting from Igbo Landing. Early American Literature, 54(1), 21–36. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26564978

CLAIR, M. (1987). The Flying Africans. Obsidian II, 2(1), 70–71. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44484893

Hovet, G. A., & Lounsberry, B. (1983). FLYING AS SYMBOL AND LEGEND IN TONI MORRISON’S “THE BLUEST EYE, SULA,” AND “SONG OF SOLOMON.” CLA Journal, 27(2), 119–140. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44321768

Rebecca Hall. (2022). Wake: The Hidden History of Women-Led Slave Revolts.

https://teachrock.org/video/toni-morrison-speaks-about-flying-africans/

“Have you ever heard of Flying Africans?” I asked a friend of mine who lives in St. Vincent and the Grenadines.

“Oh yes, you mean the Africans that flew away from enslavement?”

Bessie Coleman, the famous African American woman pilot, spoke of the freedom of flight. Some in the Oneida Indian Nation say the Black people were given providence and responsibility over the air. One traditional Maasai folk tale says that they originated when Narok, their black deity, extended their arms down from the cosmos, leading the Maasai down to earth.

Some believe Black people can fly.

The most famous American-based story of Flying Africans can be heard in the seminal film by Julie Dash, Daughters of the Dust. We learn of Igbo Landing in Georgia, a place where hundreds of years ago a group of 18 Igbo from Nigeria came to these shores in a slave ship. Once they left the ship and saw their fate, the slave auction block, they joined hands. Instead of walking together to the slave market they walked back to the water. Some say they drowned, others say they flew back to Africa.

“I’ll Fly Away”

“All God’s Chillun Had Wings”

In 2022 a new series of murals in Philadelphia are being created by Brooklyn-based artist Tatyana Fazlalizadeh, called Flight. The first one was unveiled in October 2022. https://paulcoletravels.com/2022/11/07/magical-mural-with-a-message-takes-flight-in-philadelphia/

Outfit: Flying African

Dress: hemp and organic cotton silk with water-based ink block print pressed through the lace of the wings.

Wings: upcycled lace from Center for Creative Reuse

Artist Reflections

One of the internal and external questions that most African Americans I know have asked is, “What would I have done if I was enslaved?” I often say I do not think I would have survived very long. The 1991 film Daughters of the Dust taught me the Igbo Landing story. The eighteen Igbo who, it was told, joined hands and walked back into or over the water to freedom has always resonated with me.

Upon learning that slave revolts were more likely to happen when more women were on board slave ships did not surprise me. This garment was created in honor of all of the Africans who transitioned along the Middle Passage.

Research

McDaniel, L. (1990). THE FLYING AFRICANS: EXTENT AND STRENGTH OF THE MYTH IN THE AMERICAS. Nieuwe West-Indische Gids / New West Indian Guide, 64(1/2), 28–40. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24027305

https://www.newyorker.com/culture/culture-desk/revisiting-the-legend-of-flying-africans

Barnes, P. C., & Barnes, P. (2009). Pearl Cleage’s “Flyin’ West” and the African American Motif of Flight. Obsidian, 10(1), 68–82. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44473575

HALLOCK, T. (2019). Space, Time, and Purpose in Early American Texts: Starting from Igbo Landing. Early American Literature, 54(1), 21–36. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26564978

CLAIR, M. (1987). The Flying Africans. Obsidian II, 2(1), 70–71. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44484893

Hovet, G. A., & Lounsberry, B. (1983). FLYING AS SYMBOL AND LEGEND IN TONI MORRISON’S “THE BLUEST EYE, SULA,” AND “SONG OF SOLOMON.” CLA Journal, 27(2), 119–140. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44321768

Rebecca Hall. (2022). Wake: The Hidden History of Women-Led Slave Revolts.

https://teachrock.org/video/toni-morrison-speaks-about-flying-africans/

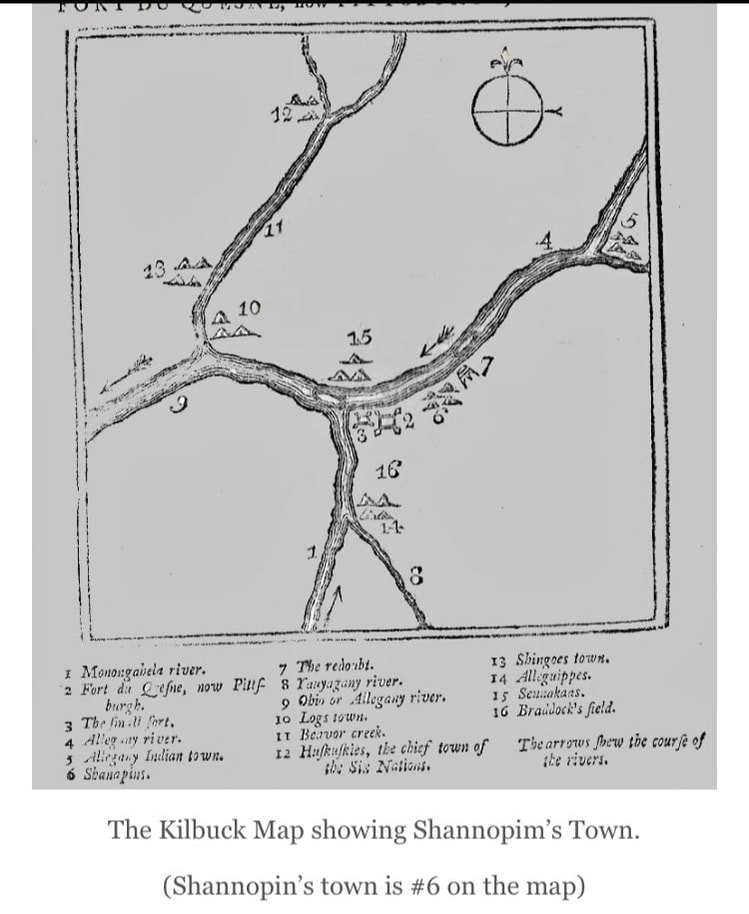

Virginia Regiment

circa 1758

Francois, an African man who escaped enslavement by the French, was stationed at Fort Duquesne and told the British in Williamsburg Virginia that the French were about to leave their fortification. This was a key incident in a series of events that led to the formation of Pittsburgh in 1758. Virginia Lieutenant Governor Robert Dinwiddie was so pleased with this information that he offered Francois his freedom.

“Forty-two Black militiamen were believed to have been with him [British General John Forbes] when Forbes renamed the fortification for the English Earl of Chatham, William Pitt.” Jerry Byrd, a general assignment reporter, created a special edition of The Pittsburgh Press Sunday Magazine, The Sunday Roto in 1982 entitled From Slaves to Statesmen….A history of Blacks in Pittsburgh.

Researching the various règlements involved in the French and Indian War in South Western Pennsylvania and what became Pittsburgh troops included: the Pennsylvania Regiment, Virginia, The Black Watch of Scotland and more.

Maria Alessandra Bollettino, Ph.D. (2009). Slavery, War, and Britain’s Atlantic Empire: Black Soldiers, Sailors, and Rebels in the Seven Years’ War, explains: “Blacks played the most essential role in martial endeavors precisely where slavery was most fundamental to society. The exigencies of worldwide war transformed a local reliance upon Black soldiers for the defense of particular colonies into an imperial dependence upon them for the security of Britain’s Atlantic empire. Following Britain’s declaration of war against France in 1756, representatives of the colonies of Georgia and South Carolina reminded the Board of Trade in London that they were menaced “not only from the Enemy from without, but also from an equally dangerous and merciless Enemy within, viz. their Negro Slaves, . . . who would doubtless be glad to purchase their Freedom at any rate or any risque.

”To afford black workers’ contribution to the British war effort its proper significance, however, it is essential to recall that mid-eighteenth-century European-style warfare employed many more laborers than warriors. Siege warfare required the sustained effort of thousands of men, and the vast majority of men on the battlefield engaged in manual labor rather than combat. While the courage and intrepidity of musket-toting regulars was touted in the aftermath of victory, commanders knew that neither they nor their arms would have made it to the field of battle without the toil of the auxiliaries.”

The Black men connected to these regiments were scouts, batmen, enslaved, free, indentured, musicians, servants, and many more. While George Washington and others famously did not want to have Black men armed, it is widely believed that when necessary they were armed.

In addition to the men connected to the regiments families also often traveled with them

Outfit

Breeches: printed hemp and organic cotton canvas made by Tereneh Idia printed at Artist Image Resource

Shirt: organic cotton and reuse ribbon by Tereneh Idia

Tie: organic cotton by Tereneh Idia

Virginia Regiment reenactment jacket: by Veteran Arms block printing by Tereneh Idia

Vintage hand-made indigo-dyed head wrap: donated by Jamie Boyle

Beads donated by Tammy Schweinhagen

Resources

Michael I. Burke, Assistant Director, Fort Pitt Museum

Michael Kraus, Curator and Historian, Soldiers and Sailors Memorial Hall & Museum Trust

Tyler Putnam, Museum of the American Revolution

Heinz History Center Archives

Larry G. Bowman. (1970). Virginia's Use of Blacks in the French and Indian War.

North Texas State University at Denton.https://journals.psu.edu/wph/article/view/3042/2873

The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography. Vol. 1, No. 3 (1894), pp. 278-287 (10 pages). Virginia Historical Society

Maria Alessandra Bollettino, Ph.D. (2009). Slavery, War, and Britain’s Atlantic Empire: Black Soldiers, Sailors, and Rebels in the Seven Years’ War

The University of Texas at Austin.

https://repositories.lib.utexas.edu/bitstream/handle/2152/ETD-UT-2009-12-543/BOLLETTINO-DISSERTATION.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

Henry Bouquet. (1951). The Papers of Henry Bouquet: The Forbes Expedition Volume II. The Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission.

circa 1758

Francois, an African man who escaped enslavement by the French, was stationed at Fort Duquesne and told the British in Williamsburg Virginia that the French were about to leave their fortification. This was a key incident in a series of events that led to the formation of Pittsburgh in 1758. Virginia Lieutenant Governor Robert Dinwiddie was so pleased with this information that he offered Francois his freedom.

“Forty-two Black militiamen were believed to have been with him [British General John Forbes] when Forbes renamed the fortification for the English Earl of Chatham, William Pitt.” Jerry Byrd, a general assignment reporter, created a special edition of The Pittsburgh Press Sunday Magazine, The Sunday Roto in 1982 entitled From Slaves to Statesmen….A history of Blacks in Pittsburgh.

Researching the various règlements involved in the French and Indian War in South Western Pennsylvania and what became Pittsburgh troops included: the Pennsylvania Regiment, Virginia, The Black Watch of Scotland and more.

Maria Alessandra Bollettino, Ph.D. (2009). Slavery, War, and Britain’s Atlantic Empire: Black Soldiers, Sailors, and Rebels in the Seven Years’ War, explains: “Blacks played the most essential role in martial endeavors precisely where slavery was most fundamental to society. The exigencies of worldwide war transformed a local reliance upon Black soldiers for the defense of particular colonies into an imperial dependence upon them for the security of Britain’s Atlantic empire. Following Britain’s declaration of war against France in 1756, representatives of the colonies of Georgia and South Carolina reminded the Board of Trade in London that they were menaced “not only from the Enemy from without, but also from an equally dangerous and merciless Enemy within, viz. their Negro Slaves, . . . who would doubtless be glad to purchase their Freedom at any rate or any risque.

”To afford black workers’ contribution to the British war effort its proper significance, however, it is essential to recall that mid-eighteenth-century European-style warfare employed many more laborers than warriors. Siege warfare required the sustained effort of thousands of men, and the vast majority of men on the battlefield engaged in manual labor rather than combat. While the courage and intrepidity of musket-toting regulars was touted in the aftermath of victory, commanders knew that neither they nor their arms would have made it to the field of battle without the toil of the auxiliaries.”

The Black men connected to these regiments were scouts, batmen, enslaved, free, indentured, musicians, servants, and many more. While George Washington and others famously did not want to have Black men armed, it is widely believed that when necessary they were armed.

In addition to the men connected to the regiments families also often traveled with them

Outfit

Breeches: printed hemp and organic cotton canvas made by Tereneh Idia printed at Artist Image Resource

Shirt: organic cotton and reuse ribbon by Tereneh Idia

Tie: organic cotton by Tereneh Idia

Virginia Regiment reenactment jacket: by Veteran Arms block printing by Tereneh Idia

Vintage hand-made indigo-dyed head wrap: donated by Jamie Boyle

Beads donated by Tammy Schweinhagen

Resources

Michael I. Burke, Assistant Director, Fort Pitt Museum

Michael Kraus, Curator and Historian, Soldiers and Sailors Memorial Hall & Museum Trust

Tyler Putnam, Museum of the American Revolution

Heinz History Center Archives

Larry G. Bowman. (1970). Virginia's Use of Blacks in the French and Indian War.

North Texas State University at Denton.https://journals.psu.edu/wph/article/view/3042/2873

The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography. Vol. 1, No. 3 (1894), pp. 278-287 (10 pages). Virginia Historical Society

Maria Alessandra Bollettino, Ph.D. (2009). Slavery, War, and Britain’s Atlantic Empire: Black Soldiers, Sailors, and Rebels in the Seven Years’ War

The University of Texas at Austin.

https://repositories.lib.utexas.edu/bitstream/handle/2152/ETD-UT-2009-12-543/BOLLETTINO-DISSERTATION.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

Henry Bouquet. (1951). The Papers of Henry Bouquet: The Forbes Expedition Volume II. The Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission.

Akiatonharónkwen

circa 1755

Akiatonharónkwen’s descendant, Daniel Bonaparte says, “One of the most important Mohawks doesn’t have one drop of Mohawk blood.” His name has been said to mean “multicolored bird” or “one who unhangs himself.”

Atiatonharónkwen, also known by the names Atayataghlonghta and Colonel Louis Cook, was born in 1737 or 1740 in what is now Saratoga New York to an African man and Abaniquis or Mohigan mother. He was almost taken and enslaved by a French soldier, but his mother cried out for help and the Haudenosaunee helped them, going so far as to adopt the family into the Mohawk Nation.

Being adopted into a Native American community means you are in, of, and with that community. Akiatonharónkwen was present at General Edward Braddock’s defeat among many other battles. He fought in the Seven Year War, the Revolutionary War, and The War of 1812. He eventually became an American ally, became a Catholic and took the name Louis Cook. He died in 1814 as a result of fighting in the War of 1812.

Thomas Cook, the seventh generation descendant of Akiatonharónkwen, says of his ancestor via email:

“The main thing about him, for our tribe historically, is that he got us our reservation in 1797. At the time when NYS was clearing Iroquois out of NYS Cook, having served the Americans as a Lieutenant Colonel in the Revolution, was the one with standing before the Americans who generally believed that all Mohawks sided with the British and should be forced from American territory.

Although frustrated with the intransigence of the American treaty commissioners, he and his delegation did get a federal treaty for the land we hold today. The treaty was ratified by Congress, placing us within Article VI of the US Constitution that states ‘Treaties made under the authority of the US shall be the supreme law of the land; and every court in any jurisdiction thereof shall abide by it.’ So, we have sovereignty to have and to depend on.”

Outfit

Breeches: printed hemp and organic cotton canvas made by Tereneh Idia printed at Artist Image Resource

Shirt: organic cotton by Tereneh Idia

Deerskin tunic by Tereneh Idia

Hand-beaded leather belt and garters: deerskin and glass beads by Tereneh Idia, some beads donated by Tammy Schweinhagen

Wool leggings: made from vintage wool blanket by Tereneh Idia

Porcupine headdress by Veteran Arms (Note: Mohawk headdress including the Haudenosaunee gahsdo:wah include three eagle feathers, as a non-native person I did not think it was appropriate for me to procure eagle feathers.)

Artist Reflections

Standing in the hall of Braddock’s Battlefield Museum, I stopped and stared at a painting that, to me, was all about the Indigenous man just left of center.

The more I learned about this remarkable person, the more I wished I had known about him all along. Here was a man who had been saved from enslavement by the Haudenosaunee and adopted by the Mohawk. That process means “blood” does not matter. He is Black, he is African, and he is Mohawk.

For this reason I wanted to include him in this exhibition, to juxtapose his service with the French with that of his free and enslaved African brothers and sisters who served with the British. Throughout what became the United States, Africans were adopted, saved, enslaved, and in community with the Indigenous of these lands.

Much more is needed to learn about this complex familial relationship. As a designer who works with Indigenous Africans and peoples of the Americas I am especially interested in this history, this present, and what the future could be. In fact the final piece for this exhibition gives a hint to my daydreaming.

Resources

Braddock’s Battlefield. https://www.braddocksbattlefield.org/

Bushy Run Battlefield. https://bushyrunbattlefield.com/

Jordan Haworth. (2021). How a Black Abenaki man shaped U.S. history, and Akwesasne's

https://www.thewhig.com/news/local-news/how-a-black-abenaki-man-shaped-u-s-history-and-akwesasnes

Darren Bonaparte. (2013). A Bird of Many Colors The Life and Times of Colonel Louis Cook

.The Eastern Door.

http://wampumchronicles.com/birdofmanycolors.html

Tom Cook, President of Kahwatsi:re Society.

http://www.wampumchronicles.com/

Louis Cook: A French and Indian Warrior. http://www.wampumchronicles.com/frenchandindianwarrior.html

Louis Cook: A “Colonel” of Truth? http://www.wampumchronicles.com/coloneloftruth.html

Atayataghlonghta – Colonel Louis Joseph Cook

https://www.nps.gov/people/atayataghlonghta-lewis-cook.htm

ATIATOHARONGWEN (Thiathoharongouan, meaning his body is taken down from hanging or one who pulls down the people; also known as Louis Atayataghronghta, Louis Cook, and Colonel Louis), Mohawk chief; b. c. 1740 in Saratoga (Schuylerville, N.Y.); d. October 1814 on the Niagara frontier.http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/atiatoharongwen_5E.html

Reverend Eleazer Williams. c. 1851. The Life of Colonel Louis Cook

http://www.wampumchronicles.com/colonellouis.html

circa 1755

Akiatonharónkwen’s descendant, Daniel Bonaparte says, “One of the most important Mohawks doesn’t have one drop of Mohawk blood.” His name has been said to mean “multicolored bird” or “one who unhangs himself.”

Atiatonharónkwen, also known by the names Atayataghlonghta and Colonel Louis Cook, was born in 1737 or 1740 in what is now Saratoga New York to an African man and Abaniquis or Mohigan mother. He was almost taken and enslaved by a French soldier, but his mother cried out for help and the Haudenosaunee helped them, going so far as to adopt the family into the Mohawk Nation.

Being adopted into a Native American community means you are in, of, and with that community. Akiatonharónkwen was present at General Edward Braddock’s defeat among many other battles. He fought in the Seven Year War, the Revolutionary War, and The War of 1812. He eventually became an American ally, became a Catholic and took the name Louis Cook. He died in 1814 as a result of fighting in the War of 1812.

Thomas Cook, the seventh generation descendant of Akiatonharónkwen, says of his ancestor via email:

“The main thing about him, for our tribe historically, is that he got us our reservation in 1797. At the time when NYS was clearing Iroquois out of NYS Cook, having served the Americans as a Lieutenant Colonel in the Revolution, was the one with standing before the Americans who generally believed that all Mohawks sided with the British and should be forced from American territory.

Although frustrated with the intransigence of the American treaty commissioners, he and his delegation did get a federal treaty for the land we hold today. The treaty was ratified by Congress, placing us within Article VI of the US Constitution that states ‘Treaties made under the authority of the US shall be the supreme law of the land; and every court in any jurisdiction thereof shall abide by it.’ So, we have sovereignty to have and to depend on.”

Outfit

Breeches: printed hemp and organic cotton canvas made by Tereneh Idia printed at Artist Image Resource

Shirt: organic cotton by Tereneh Idia

Deerskin tunic by Tereneh Idia

Hand-beaded leather belt and garters: deerskin and glass beads by Tereneh Idia, some beads donated by Tammy Schweinhagen

Wool leggings: made from vintage wool blanket by Tereneh Idia

Porcupine headdress by Veteran Arms (Note: Mohawk headdress including the Haudenosaunee gahsdo:wah include three eagle feathers, as a non-native person I did not think it was appropriate for me to procure eagle feathers.)

Artist Reflections

Standing in the hall of Braddock’s Battlefield Museum, I stopped and stared at a painting that, to me, was all about the Indigenous man just left of center.

The more I learned about this remarkable person, the more I wished I had known about him all along. Here was a man who had been saved from enslavement by the Haudenosaunee and adopted by the Mohawk. That process means “blood” does not matter. He is Black, he is African, and he is Mohawk.

For this reason I wanted to include him in this exhibition, to juxtapose his service with the French with that of his free and enslaved African brothers and sisters who served with the British. Throughout what became the United States, Africans were adopted, saved, enslaved, and in community with the Indigenous of these lands.

Much more is needed to learn about this complex familial relationship. As a designer who works with Indigenous Africans and peoples of the Americas I am especially interested in this history, this present, and what the future could be. In fact the final piece for this exhibition gives a hint to my daydreaming.

Resources

Braddock’s Battlefield. https://www.braddocksbattlefield.org/

Bushy Run Battlefield. https://bushyrunbattlefield.com/

Jordan Haworth. (2021). How a Black Abenaki man shaped U.S. history, and Akwesasne's

https://www.thewhig.com/news/local-news/how-a-black-abenaki-man-shaped-u-s-history-and-akwesasnes

Darren Bonaparte. (2013). A Bird of Many Colors The Life and Times of Colonel Louis Cook

.The Eastern Door.

http://wampumchronicles.com/birdofmanycolors.html

Tom Cook, President of Kahwatsi:re Society.

http://www.wampumchronicles.com/

Louis Cook: A French and Indian Warrior. http://www.wampumchronicles.com/frenchandindianwarrior.html

Louis Cook: A “Colonel” of Truth? http://www.wampumchronicles.com/coloneloftruth.html

Atayataghlonghta – Colonel Louis Joseph Cook

https://www.nps.gov/people/atayataghlonghta-lewis-cook.htm

ATIATOHARONGWEN (Thiathoharongouan, meaning his body is taken down from hanging or one who pulls down the people; also known as Louis Atayataghronghta, Louis Cook, and Colonel Louis), Mohawk chief; b. c. 1740 in Saratoga (Schuylerville, N.Y.); d. October 1814 on the Niagara frontier.http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/atiatoharongwen_5E.html

Reverend Eleazer Williams. c. 1851. The Life of Colonel Louis Cook

http://www.wampumchronicles.com/colonellouis.html

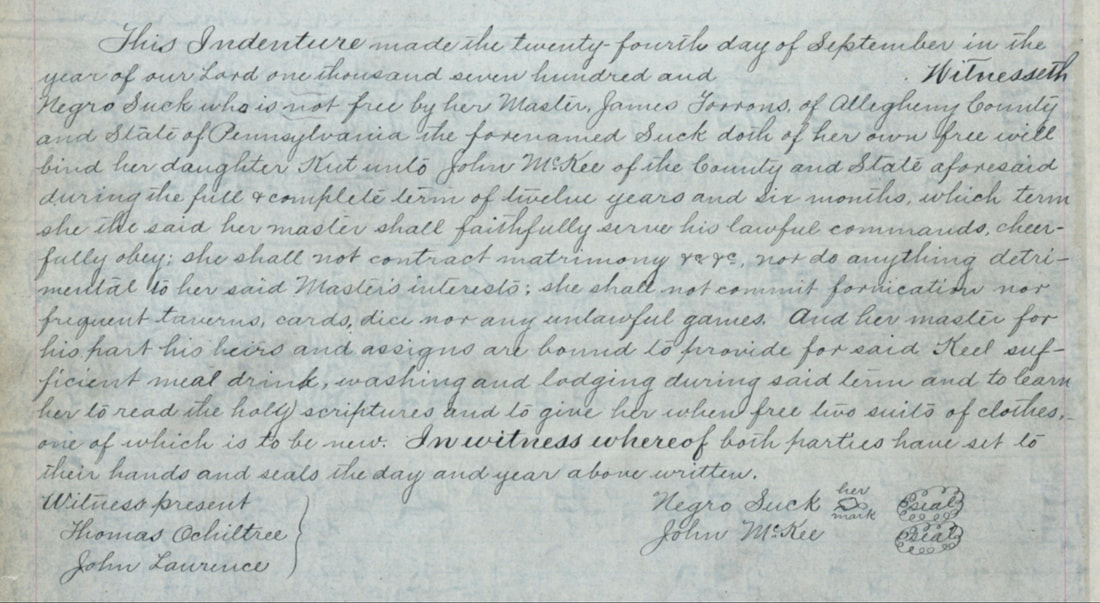

Negro “Sukey” Suck

circa 1790

“This Indenture made the twenty-fourth day of September in the year of our Lord one thousand seven hundred and Witnesseth Negro Suck who is not free by her Master James Torrons, of Allegheny County and State of Pennsylvania the forenamed Suck doth of her own free will bind her daughter Kut unto John McKee of the County and State aforesaid during the full & complete term of twelve years and Six months, which term she the said her master shall faithfully serve his lawful commands, cheerfully obey…”

In 1790, Peter Costco bought his freedom from John McKee, the founder of McKeesport, for 100 pounds. That same year, McKee indentured Kut from her enslaved mother, Negro Suck.

These documents are found in Allegheny County records.

Interestingly, there is a marker near PPG Place noting Pittsburgh’s Underground Railroad heritage. Yet there is no marker, no monument, no public notation or space acknowledging Pittsburgh’s enslavement heritage.

Pennsylvania enslavement heritage may begin in 1630’s. The Delaware River Valley reportedly had enslaved Africans held by the Swedish, the Danish, and the Finnish. In 1684, the Isabella slave ship landed in Philadelphia.

In 1712, the Pennsylvania assembly imposed a high import tax for enslaved peoples, which the British repealed. Pittsburgh and the region went through many phases of enslavement and attempts at abolition. In 1780, Pennsylvania passed a “gradual abolition of slavery act.” Western Pennsylvania enslavers were so committed to enslavement of Africans they were able to get a two year extension.

However in 1790, ten years after the “gradual abolition act,” there were nearly 900 documented enslaved in Pittsburgh. One can only imagine the true number of enslaved Africans in this region over the course of hundreds of years. Additional acts and laws had to be passed to close loopholes. One such loophole allowed for the transportation of enslaved pregnant women to Virginia, so that their child would be literally born enslaved.

In fact, even free Blacks were under constant threat of being kidnapped and enslaved into the 1800’s. The title of the project Free At Last? Includes a question mark for a reason.The name Suck is believed to be based on the Wolof name Sukey, while Kut has West African and Creole heritage meaning “quite” or “graceful lily.” Slaves were often given names like Negro, Mulatto and the like.

Outfit

Sukey is dressed in the C3 flag fabric in organic cotton. She is wearing a head wrap made from fabric found in Kenya. There is a small red “K” painted on her dress near her heart.

Artist Reflections

How could a mother indenture her own daughter? I thought about this for a long time. I sat and spoke to Sukey often. I cried with her. I came to understand that even though the document she placed her mark said “of free will…,” she was an enslaved woman. Because it was ten years after the “gradual abolition” act was passed, enslavement was happening. For Sukey this 12 year and 6 month indenture was the best she could do for daughter given her circumstances.

There was a Torrens train stop near what is now Wilkinsburg. Wilkins was one of the signatories on the aforementioned indenture act. Wilkins owned lots of land, and it seems Torrens was right next to him or potentially on that land as well. Torrens may have been in the glass and window making business, and the Torrens family also owned land in downtown Pittsburgh, where PPG Place is now. I have no idea if there is a connection. More research is needed, including what happened to Sukey and Kut.

References

Free At Last? http://exhibit.library.pitt.edu/freeatlast/papers_listing.html

Joe William Trotter Jr and Eric Ledell Smith. (1997). African Americans in Pennsylvania Shifting Historical Perspective.The Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission and The Pennsylvania State University Press.

Laurence A Glasco. (2004). The WPA History of the Negro in Pittsburgh edited by University of Pittsburgh Press

Alan Dundee. (1990). Mother Wit from the Laughing Barrel: Readings in the Interpretation of Afro-American Folklore University Press of Mississippi

Heinz History Center Archives

The article from the Pittsburgh City Paper in the resources below is unfortunate in tone. However, it does offer some good information. https://www.pghcitypaper.com/pittsburgh/in-the-days-when-slavery-was-legal-in-pennsylvania-how-many-slaves-were-owned-here/Content?oid=1335540

circa 1790

“This Indenture made the twenty-fourth day of September in the year of our Lord one thousand seven hundred and Witnesseth Negro Suck who is not free by her Master James Torrons, of Allegheny County and State of Pennsylvania the forenamed Suck doth of her own free will bind her daughter Kut unto John McKee of the County and State aforesaid during the full & complete term of twelve years and Six months, which term she the said her master shall faithfully serve his lawful commands, cheerfully obey…”

In 1790, Peter Costco bought his freedom from John McKee, the founder of McKeesport, for 100 pounds. That same year, McKee indentured Kut from her enslaved mother, Negro Suck.

These documents are found in Allegheny County records.

Interestingly, there is a marker near PPG Place noting Pittsburgh’s Underground Railroad heritage. Yet there is no marker, no monument, no public notation or space acknowledging Pittsburgh’s enslavement heritage.

Pennsylvania enslavement heritage may begin in 1630’s. The Delaware River Valley reportedly had enslaved Africans held by the Swedish, the Danish, and the Finnish. In 1684, the Isabella slave ship landed in Philadelphia.

In 1712, the Pennsylvania assembly imposed a high import tax for enslaved peoples, which the British repealed. Pittsburgh and the region went through many phases of enslavement and attempts at abolition. In 1780, Pennsylvania passed a “gradual abolition of slavery act.” Western Pennsylvania enslavers were so committed to enslavement of Africans they were able to get a two year extension.

However in 1790, ten years after the “gradual abolition act,” there were nearly 900 documented enslaved in Pittsburgh. One can only imagine the true number of enslaved Africans in this region over the course of hundreds of years. Additional acts and laws had to be passed to close loopholes. One such loophole allowed for the transportation of enslaved pregnant women to Virginia, so that their child would be literally born enslaved.

In fact, even free Blacks were under constant threat of being kidnapped and enslaved into the 1800’s. The title of the project Free At Last? Includes a question mark for a reason.The name Suck is believed to be based on the Wolof name Sukey, while Kut has West African and Creole heritage meaning “quite” or “graceful lily.” Slaves were often given names like Negro, Mulatto and the like.

Outfit

Sukey is dressed in the C3 flag fabric in organic cotton. She is wearing a head wrap made from fabric found in Kenya. There is a small red “K” painted on her dress near her heart.

Artist Reflections

How could a mother indenture her own daughter? I thought about this for a long time. I sat and spoke to Sukey often. I cried with her. I came to understand that even though the document she placed her mark said “of free will…,” she was an enslaved woman. Because it was ten years after the “gradual abolition” act was passed, enslavement was happening. For Sukey this 12 year and 6 month indenture was the best she could do for daughter given her circumstances.

There was a Torrens train stop near what is now Wilkinsburg. Wilkins was one of the signatories on the aforementioned indenture act. Wilkins owned lots of land, and it seems Torrens was right next to him or potentially on that land as well. Torrens may have been in the glass and window making business, and the Torrens family also owned land in downtown Pittsburgh, where PPG Place is now. I have no idea if there is a connection. More research is needed, including what happened to Sukey and Kut.

References

Free At Last? http://exhibit.library.pitt.edu/freeatlast/papers_listing.html

Joe William Trotter Jr and Eric Ledell Smith. (1997). African Americans in Pennsylvania Shifting Historical Perspective.The Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission and The Pennsylvania State University Press.

Laurence A Glasco. (2004). The WPA History of the Negro in Pittsburgh edited by University of Pittsburgh Press

Alan Dundee. (1990). Mother Wit from the Laughing Barrel: Readings in the Interpretation of Afro-American Folklore University Press of Mississippi

Heinz History Center Archives

The article from the Pittsburgh City Paper in the resources below is unfortunate in tone. However, it does offer some good information. https://www.pghcitypaper.com/pittsburgh/in-the-days-when-slavery-was-legal-in-pennsylvania-how-many-slaves-were-owned-here/Content?oid=1335540

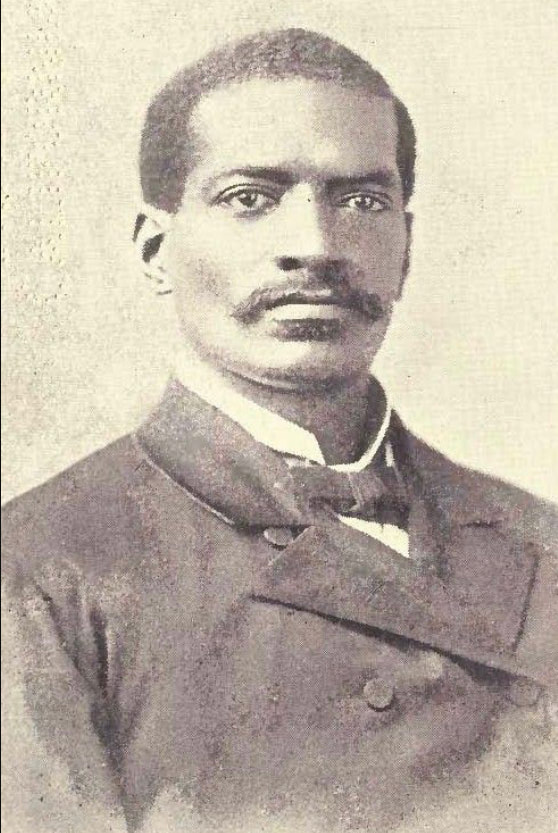

John Vashon

circa 1800s

“Black Jack,” Captain Patrick Jack, Charles Richards, and Benjamin Richards. A scout and guide, a tavern keeper, a land merchant and cattle dealer. Four Black free men among the signatories creating Allegheny County.

The 1800s for African Americans of Pittsburgh is much like now; A Tale of Two Cities, but in this case maybe three. Free men, women, and children, albeit in constant fear of losing that freedom, lived alongside enslaved and indentured African Americans.

On one hand, the 1800s created the opportunity to become entrepreneurs, educators, and more. After researching the businesses in downtown Pittsburgh one could argue there were more Black owned businesses in the 1800s in the golden triangle than there are now. Barber shops, tailors, bath houses, taverns, and oyster houses, among others. On the other hand, as Jerry Bird notes in From Slaves to Statesmen: A History of Blacks in Pittsburgh, the city is the “midwife” to Jim Crow law and racial segregation.

One entrepreneur, John Bathan Vashon, became one of the most important Black leaders in the country and he did most of this work in Pittsburgh.

John Vashon was born in Virginia in 1792. His mother was enslaved and his father was a white Frenchman. At the age of 20, he served in the navy in the War of 1812, was taken prisoner, traded for a British soldier, then returned to Virginia. In 1829, he moved with his wife and son from Carlisle to Pittsburgh.

Here he built a fortune from barber shops and bath houses, building the first bath house for women west of the Appalachians. But he did not end there. He was also an abolitionist, founder, and conductor on the Underground Railroad. He is one of the many under-sung heroes in Pittsburgh.

Outfit

Seersucker vest and trousers made from upcycled fabric from Center for Creative Reuse by Tereneh Idia

Late 1890-early 1900s vintage cotton shirts procured via LooneyEuneys on Etsy. Hemp and organic cotton C3 flag printed collar by Tereneh Idia

Shirt garters ribbon and vintage hooks by Tereneh Idia

Nautical themed compass tie pin inspired by Vashon’s naval and Underground Railroad service by Shelley Cooper Jewelry

Artist Reflections

It seems that the rest of the country knows more about John Vashon than Pittsburgh does. There is Vashon High School in St Louis Missouri, which opened in 1927. The University of Chicago’s archives includes letters from William Lloyd Garrison to John Vashon in the 1830’s. His son George Vashon established Avery College in Pittsburgh, proof of what generational wealth and opportunity may foster. And the impact of what happens when it does not.

Tributes to Vashon’s work and legacy as well as the contributions of his descendants seems overdue.

References

John Bathan Vashon, Seaman, and Abolitionist.

https://aaregistry.org/story/john-bathan-vashon-seaman-and-abolitionist/

William J Switala. (2008). Underground Railroad in Pennsylvania Second Edition by Stackpole Books.

Joe William Trotter Jr and Eric Ledell Smith. (1997). African Americans in Pennsylvania Shifting Historical Perspective. editors: Joe William Trotter Jr and Eric Ledell Smith The Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission and The Pennsylvania State University Press. 1997

Laurence A Glasco. (2004). The WPA History of the Negro in Pittsburgh. University of Pittsburgh Press

The Civil War in Pennsylvania The African American Experience editor Samuel Black Senator John Heinz History Center 2013 (including for context of military service)

Heinz History Center Archives

circa 1800s

“Black Jack,” Captain Patrick Jack, Charles Richards, and Benjamin Richards. A scout and guide, a tavern keeper, a land merchant and cattle dealer. Four Black free men among the signatories creating Allegheny County.

The 1800s for African Americans of Pittsburgh is much like now; A Tale of Two Cities, but in this case maybe three. Free men, women, and children, albeit in constant fear of losing that freedom, lived alongside enslaved and indentured African Americans.

On one hand, the 1800s created the opportunity to become entrepreneurs, educators, and more. After researching the businesses in downtown Pittsburgh one could argue there were more Black owned businesses in the 1800s in the golden triangle than there are now. Barber shops, tailors, bath houses, taverns, and oyster houses, among others. On the other hand, as Jerry Bird notes in From Slaves to Statesmen: A History of Blacks in Pittsburgh, the city is the “midwife” to Jim Crow law and racial segregation.

One entrepreneur, John Bathan Vashon, became one of the most important Black leaders in the country and he did most of this work in Pittsburgh.

John Vashon was born in Virginia in 1792. His mother was enslaved and his father was a white Frenchman. At the age of 20, he served in the navy in the War of 1812, was taken prisoner, traded for a British soldier, then returned to Virginia. In 1829, he moved with his wife and son from Carlisle to Pittsburgh.

Here he built a fortune from barber shops and bath houses, building the first bath house for women west of the Appalachians. But he did not end there. He was also an abolitionist, founder, and conductor on the Underground Railroad. He is one of the many under-sung heroes in Pittsburgh.

Outfit

Seersucker vest and trousers made from upcycled fabric from Center for Creative Reuse by Tereneh Idia

Late 1890-early 1900s vintage cotton shirts procured via LooneyEuneys on Etsy. Hemp and organic cotton C3 flag printed collar by Tereneh Idia

Shirt garters ribbon and vintage hooks by Tereneh Idia

Nautical themed compass tie pin inspired by Vashon’s naval and Underground Railroad service by Shelley Cooper Jewelry

Artist Reflections

It seems that the rest of the country knows more about John Vashon than Pittsburgh does. There is Vashon High School in St Louis Missouri, which opened in 1927. The University of Chicago’s archives includes letters from William Lloyd Garrison to John Vashon in the 1830’s. His son George Vashon established Avery College in Pittsburgh, proof of what generational wealth and opportunity may foster. And the impact of what happens when it does not.

Tributes to Vashon’s work and legacy as well as the contributions of his descendants seems overdue.

References

John Bathan Vashon, Seaman, and Abolitionist.

https://aaregistry.org/story/john-bathan-vashon-seaman-and-abolitionist/

William J Switala. (2008). Underground Railroad in Pennsylvania Second Edition by Stackpole Books.

Joe William Trotter Jr and Eric Ledell Smith. (1997). African Americans in Pennsylvania Shifting Historical Perspective. editors: Joe William Trotter Jr and Eric Ledell Smith The Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission and The Pennsylvania State University Press. 1997

Laurence A Glasco. (2004). The WPA History of the Negro in Pittsburgh. University of Pittsburgh Press

The Civil War in Pennsylvania The African American Experience editor Samuel Black Senator John Heinz History Center 2013 (including for context of military service)

Heinz History Center Archives

Great Migration Family

circa 1920s

Between 1910 and 1960, over 4.5 million African Americans left the south in search of what late novelist and poet Richard Wright called “the warmth of other suns.”

Pennsylvania saw Blacks from Virginia, North and South Carolina and Georgia entering Philadelphia. While Pittsburgh welcomed folks from Alabama, Tennessee, Louisiana, and Mississippi, the African American population of Allegheny County in 1910 was 34,217. In 20 years, that number grew to 83,326. The Urban League reported that between 1918 and1923, approximately 25,000 African Americans came to Pittsburgh.

Black newspapers like the Pittsburgh Courier were a key part of this process. By 1930, two-thirds of the Black Population in Pittsburgh were from outside the region.

Bold Improvisations: 120 Years of African American Quilts was an exhibition at the Manchester Craftsmen's Guild in 2009. The Heinz History Center created an oral history featuring the artists in that exhibition. Something that every group exhibition should do, in my opinion.

One of these oral histories told the story of how a Black family came to Pittsburgh. It involved a white bar owner, his daughter, and Black male employee who did not welcome her sexual advances. The woman falsely claimed the African American man attacked her, which meant he had to flee the town immediately. This man was the father of one of the now Pittsburgh-based quilters.

Outfits

Mom: vintage Peter Pan cotton fabric featuring dogwood flowers by Tereneh Idia

Enameled cameo-map brooch made by Tereneh Idia

Child 1: vintage Peter Pan cotton fabric by Tereneh Idia

Pennsylvania Regiment French and Indian War reenactment hat by Peck 2 on eBay.

Child 2: vintage Peter Pan cotton fabric by Tereneh Idia

Rag doll by Tereneh Idia

Quilt: The Weed Wack for Zell Strong by Ada S. Cyrus 2016 cotton scrap quilt

Artist Reflections

This Great Migration story, while inspired by the story read at the Heinz History Center, takes a different approach. For every Black family who moved safely North, some didn’t make it. We do not know how many lives were lost to state-sanctioned violence, the violence of whiteness, and the weaponizing of white womanhood. For this reason, this family travels north without their husband, without their father. The mother wears a brooch showing the silhouette of her lost beloved's face, as well as their route north to Pittsburgh.

Because they had to move in haste, and because of where they lived in the south they did not have winter coats, they traveled with a quilt to provide warmth on their journey to Pittsburgh.

I am grateful to many Black women artists, especially for this portion of the C3 exhibition. Firstly, all of the artists who participated in the Bold Improvisation exhibition. Second, Tanya Crane who taught me how to enamel. Third, to Ada Cyrus for loaning one of her amazing quilts to the exhibition.

Ms Ada says of this quilt: “It was made for a child in the family, they pulled up some of the corners to see what was inside.”

Resources

Isabel Wilkerson. (2011). The Warmth of Other Suns: The Epic Story of America’s Great Migration Vintage Publishing.

Peter Gottlieb. (1997). Making Their Own Way: Southern Black’s Migration to Pittsburgh, 1916-1930 University of Illinois Press.

'Bold Improvisation : 120 Years of African American quilts. Oral history project and exhibit' Call number: 2009.0084. Heinz History Center Archives Historical Society of Western Pennsylvania

From Slaves to Statesmen A History of Blacks in Pittsburgh

August Wilson and the Great Migration to Pittsburgh.

https://www.hartfordstage.org/stagenotes/piano-lesson/migration-to-pittsburgh/

Chuck Biedka.

Black migration making great impact on Pittsburgh region

https://triblive.com/local/valley-news-dispatch/black-migration-making-great-impact-on-pittsburgh-region/

The Frick Pittsburgh. Pittsburgh and the Great Migration: Black Mobility and the Automobile

(May 6, 2023 - February 4, 2024)

https://www.thefrickpittsburgh.org/Exhibition-Pittsburgh-And-The-Great-Migration

Kalonji Johnson, Director of the Office of Policy, Pennsylvania Department of State. (2019).

The Philadelphia Tribune and The Pittsburgh Courier: Two historic African American Newspaper with roots in the Great Migration

https://www.dos.pa.gov/SimplyStated/Pages/Article.aspx?post=17

circa 1920s

Between 1910 and 1960, over 4.5 million African Americans left the south in search of what late novelist and poet Richard Wright called “the warmth of other suns.”

Pennsylvania saw Blacks from Virginia, North and South Carolina and Georgia entering Philadelphia. While Pittsburgh welcomed folks from Alabama, Tennessee, Louisiana, and Mississippi, the African American population of Allegheny County in 1910 was 34,217. In 20 years, that number grew to 83,326. The Urban League reported that between 1918 and1923, approximately 25,000 African Americans came to Pittsburgh.

Black newspapers like the Pittsburgh Courier were a key part of this process. By 1930, two-thirds of the Black Population in Pittsburgh were from outside the region.

Bold Improvisations: 120 Years of African American Quilts was an exhibition at the Manchester Craftsmen's Guild in 2009. The Heinz History Center created an oral history featuring the artists in that exhibition. Something that every group exhibition should do, in my opinion.

One of these oral histories told the story of how a Black family came to Pittsburgh. It involved a white bar owner, his daughter, and Black male employee who did not welcome her sexual advances. The woman falsely claimed the African American man attacked her, which meant he had to flee the town immediately. This man was the father of one of the now Pittsburgh-based quilters.

Outfits

Mom: vintage Peter Pan cotton fabric featuring dogwood flowers by Tereneh Idia

Enameled cameo-map brooch made by Tereneh Idia

Child 1: vintage Peter Pan cotton fabric by Tereneh Idia

Pennsylvania Regiment French and Indian War reenactment hat by Peck 2 on eBay.

Child 2: vintage Peter Pan cotton fabric by Tereneh Idia

Rag doll by Tereneh Idia

Quilt: The Weed Wack for Zell Strong by Ada S. Cyrus 2016 cotton scrap quilt

Artist Reflections

This Great Migration story, while inspired by the story read at the Heinz History Center, takes a different approach. For every Black family who moved safely North, some didn’t make it. We do not know how many lives were lost to state-sanctioned violence, the violence of whiteness, and the weaponizing of white womanhood. For this reason, this family travels north without their husband, without their father. The mother wears a brooch showing the silhouette of her lost beloved's face, as well as their route north to Pittsburgh.

Because they had to move in haste, and because of where they lived in the south they did not have winter coats, they traveled with a quilt to provide warmth on their journey to Pittsburgh.

I am grateful to many Black women artists, especially for this portion of the C3 exhibition. Firstly, all of the artists who participated in the Bold Improvisation exhibition. Second, Tanya Crane who taught me how to enamel. Third, to Ada Cyrus for loaning one of her amazing quilts to the exhibition.

Ms Ada says of this quilt: “It was made for a child in the family, they pulled up some of the corners to see what was inside.”

Resources

Isabel Wilkerson. (2011). The Warmth of Other Suns: The Epic Story of America’s Great Migration Vintage Publishing.

Peter Gottlieb. (1997). Making Their Own Way: Southern Black’s Migration to Pittsburgh, 1916-1930 University of Illinois Press.

'Bold Improvisation : 120 Years of African American quilts. Oral history project and exhibit' Call number: 2009.0084. Heinz History Center Archives Historical Society of Western Pennsylvania

From Slaves to Statesmen A History of Blacks in Pittsburgh

August Wilson and the Great Migration to Pittsburgh.

https://www.hartfordstage.org/stagenotes/piano-lesson/migration-to-pittsburgh/

Chuck Biedka.

Black migration making great impact on Pittsburgh region

https://triblive.com/local/valley-news-dispatch/black-migration-making-great-impact-on-pittsburgh-region/

The Frick Pittsburgh. Pittsburgh and the Great Migration: Black Mobility and the Automobile

(May 6, 2023 - February 4, 2024)

https://www.thefrickpittsburgh.org/Exhibition-Pittsburgh-And-The-Great-Migration

Kalonji Johnson, Director of the Office of Policy, Pennsylvania Department of State. (2019).

The Philadelphia Tribune and The Pittsburgh Courier: Two historic African American Newspaper with roots in the Great Migration

https://www.dos.pa.gov/SimplyStated/Pages/Article.aspx?post=17

Thaddeus Mosley, Sr.

circa 1930s

Mosley family lore tells of farms and coal mines. An uncle who went to university before anyone else in the family. An aunt who was so light that her bridegroom asked on their wedding day why there were so many “negroes present” at their wedding. We also hear of hundreds of acres of farmland lost. Veteran benefits unpaid or at the very least paid less.

One of my favorite stories is a contemporary one. The granddaughter of a former Frick mine coal miner shows her art at the Frick Museum of Pittsburgh. I wonder what my grandfather would think about that one.

Thaddeus Mosley, Sr. began coal mining at the age of 16 according to his son Thad Mosley, Jr., though he doesn’t go by junior very often if at all, now. My grandfather died in his 50’s so I never got a chance to meet him.

I have heard that he was so strong, he would bet that if you weighed 150 pounds or less he could lift you with one arm. When my grandmother bought a piano he called out, “Helen, how does the piano sound?” Supposedly, after learning that the piano movers could not in fact move the piano, he took one end of the piano and hauled it up himself.

Another favorite story is set in the town Number Five Mine, Pennsylvania near present day Grove City. Mosley, Sr. was a union organizer. As such, the mining company was not a fan. To intimidate organizing, they would send guards to their home and shoot rounds of buckshot at the house. My father and his siblings would hide under the bed while my grandfather shot back from the living room window and my grandmother shot from the kitchen window. One of my aunts was hit once, and lived her whole life with buckshot in her leg.

My grandfather also ran moonshine for a neighbor who brewed it in their home. My grandparents were amazing farmers, as both their families had farms at one point. They grew food so they did not have to pay money back to the company to feed their family.

Outfit

vintage Carhartt overalls procured via eBay. Block print by Tereneh Idia.

Organic cotton Henley shirt by Tereneh Idia

Dried floral arrangement by GrassRoots Health via Etsy.

Artist Reflections

I wanted to include something that showed some of the multifaceted life of my coal miner grandfather. There is a nod to his agricultural interests and talents, as well as the lost legacy of larger scale farming and land ownership.

I related mainly family stories about my grandfather, but below I list additional references to learn more about African American coal miners. Most of the resources are coming from West Virginia rather than from Pennsylvania. Again, more whitewashing of history. More research is needed on the role African Americans played in both the steel and coal mining industries.

References

Peter Gottlieb. (1987). Black miners and the 1925–28 bituminous coal strike: The colored committee of non-union miners, montour mine No. 1, Pittsburgh Coal Company, Labor History, 28:2, 233-241, DOI: 10.1080/00236568700890131

African American Coal Miners: Helen, WV. https://www.nps.gov/neri/planyourvisit/african-american-coal-miners-helen-wv.htm

African American Workers and the Appalachian Coal Industry.

https://wvupressonline.com/african-american-workers-and-the-appalachian-coal-industry

Stephen Starr. (2022). The forgotten history of the US' African American coal towns https://www.bbc.com/travel/article/20221023-the-forgotten-history-of-the-us-african-american-coal-towns

Black Steel Workers, Erased. https://thebraddockinclusionproject.com/black-american-steelworkers-erased/

Blacks help drive steel revolution in Pittsburgh. https://pittnews.com/article/30520/archives/blacks-help-drive-steel-revolution-in-pittsburgh/

John Bodnar, Roger Simon and Michael P. Weber. (1983) Lives Of Their Own: Blacks, Italians and Poles in Pittsburgh, 1900-1960 University of Illinois Press

circa 1930s

Mosley family lore tells of farms and coal mines. An uncle who went to university before anyone else in the family. An aunt who was so light that her bridegroom asked on their wedding day why there were so many “negroes present” at their wedding. We also hear of hundreds of acres of farmland lost. Veteran benefits unpaid or at the very least paid less.

One of my favorite stories is a contemporary one. The granddaughter of a former Frick mine coal miner shows her art at the Frick Museum of Pittsburgh. I wonder what my grandfather would think about that one.

Thaddeus Mosley, Sr. began coal mining at the age of 16 according to his son Thad Mosley, Jr., though he doesn’t go by junior very often if at all, now. My grandfather died in his 50’s so I never got a chance to meet him.

I have heard that he was so strong, he would bet that if you weighed 150 pounds or less he could lift you with one arm. When my grandmother bought a piano he called out, “Helen, how does the piano sound?” Supposedly, after learning that the piano movers could not in fact move the piano, he took one end of the piano and hauled it up himself.

Another favorite story is set in the town Number Five Mine, Pennsylvania near present day Grove City. Mosley, Sr. was a union organizer. As such, the mining company was not a fan. To intimidate organizing, they would send guards to their home and shoot rounds of buckshot at the house. My father and his siblings would hide under the bed while my grandfather shot back from the living room window and my grandmother shot from the kitchen window. One of my aunts was hit once, and lived her whole life with buckshot in her leg.

My grandfather also ran moonshine for a neighbor who brewed it in their home. My grandparents were amazing farmers, as both their families had farms at one point. They grew food so they did not have to pay money back to the company to feed their family.

Outfit

vintage Carhartt overalls procured via eBay. Block print by Tereneh Idia.

Organic cotton Henley shirt by Tereneh Idia

Dried floral arrangement by GrassRoots Health via Etsy.

Artist Reflections

I wanted to include something that showed some of the multifaceted life of my coal miner grandfather. There is a nod to his agricultural interests and talents, as well as the lost legacy of larger scale farming and land ownership.

I related mainly family stories about my grandfather, but below I list additional references to learn more about African American coal miners. Most of the resources are coming from West Virginia rather than from Pennsylvania. Again, more whitewashing of history. More research is needed on the role African Americans played in both the steel and coal mining industries.

References

Peter Gottlieb. (1987). Black miners and the 1925–28 bituminous coal strike: The colored committee of non-union miners, montour mine No. 1, Pittsburgh Coal Company, Labor History, 28:2, 233-241, DOI: 10.1080/00236568700890131

African American Coal Miners: Helen, WV. https://www.nps.gov/neri/planyourvisit/african-american-coal-miners-helen-wv.htm

African American Workers and the Appalachian Coal Industry.

https://wvupressonline.com/african-american-workers-and-the-appalachian-coal-industry

Stephen Starr. (2022). The forgotten history of the US' African American coal towns https://www.bbc.com/travel/article/20221023-the-forgotten-history-of-the-us-african-american-coal-towns

Black Steel Workers, Erased. https://thebraddockinclusionproject.com/black-american-steelworkers-erased/

Blacks help drive steel revolution in Pittsburgh. https://pittnews.com/article/30520/archives/blacks-help-drive-steel-revolution-in-pittsburgh/

John Bodnar, Roger Simon and Michael P. Weber. (1983) Lives Of Their Own: Blacks, Italians and Poles in Pittsburgh, 1900-1960 University of Illinois Press

WWII veteran

circa 1940s

“I threw my uniform in the San Francisco Bay but I kept my dog tags.”

This was my first introduction to World War II. This was my father, Thaddeus G Mosley, talking about his return from his service with the US Navy in the Solomon Islands. Apparently, you had to turn in your dog tags to qualify for veteran benefits. The fact that African American service people did not get the same benefits as whites is often reported, but the intergenerational and lasting impact of getting less than they deserved is not discussed enough. It led to lower wages, less wealth, and an inability to secure housing or attend college. If you could attend college and get a degree, you were less likely to get a job in keeping with the degree you just acquired. So the cycle of having less than you deserve continued, and still does to this very day.

This injustice was bad enough, but it was made worse if you were one of the 48,000 African American, women, or LGBTQIA+ service people who were given a Blue Discharge. This was a neither honorable or dishonorable discharge that was disproportionately leveled at Black service people and those who were thought to be homosexual. While African Americans made up around 6.5% of the army during World War II, 22% of the Blue Discharges were given to Black soldiers. While it was abolished in 1947, there were no automatic reviews to determine veteran benefits.

One such soldier is Nelson Henry, Jr. According to Temple University news, the alumni was a student at Lincoln University when he enlisted in the army in 1942. Due to an old injury and further physical strain during training, he did not pass the physical to go overseas and was discharged. He was given a Blue Discharge, named for the blue paper it was printed on. Those with that discharge, though technically not a dishonorable discharge, were “routinely denied veteran benefits.” This was the case of Mr Henry, who fought for years to get his benefits reinstated. It was not until 2019 that his discharge was upgraded to an honorable one. Mr Henry died in 2020 of complications caused by the coronavirus.

Outfit

Upcycled wool suiting material lined in synthetic blue fabric and black ribbon by Tereneh Idia

Chain and Triple V for victory charm made from upcycled chains from Center for Creative Reuse (PCCR) by Tereneh Idia

Vest from upcycled upholstery fabric from PCCR by Tereneh Idia

Tie from C3 hemp and organic cotton flag fabric by Tereneh Idia

Vintage men’s shirt from eBay

Artist Reflections

The New Pittsburgh Courier was instrumental in the “Double V for Victory” campaign, the goal of which was to defeat fascism in Europe and anti-Black racism in the United States. But how do you fight for a country who does not see you as a full citizen, a full human being?

There are documented cases of violence and even the death of Black service people returning to their home towns in America in uniform, only to be killed in that uniform. Some whites were so disturbed to see a Black man in military uniform. Imagine surviving Hitler only to be killed by your white neighbors?

For this project I added another “V,” that of ending discrimination and injustice of the LGBTQIA+ community. Often in my social justice work and writing I say, “It is never one thing.” To allow injustice to one member of our human family impacts all of us.

References

A WWII veteran’s fight to receive an honorable discharge.

https://news.temple.edu/news/2020-11-09/wwii-veteran-s-fight-receive-honorable-discharge

Nelson Henry Jr., World War II vet who fought racism in Army, dies at 96.

https://www.inquirer.com/obituaries/pa-nelson-henry-veteran-army-blue-discharge-discrimination-appeal-philadelphia-20200511.html

“Blue” Ticket

https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/blue-and-other-than-honorable-discharges.htm#:~:text=During WWII, to cut costs,African Americans, and LGBTQ servicemen.

The Blue Ticket Discharge: A Color that has Stained the Lives of WWII-Era Veterans for Over 75 Years

https://mvets.law.gmu.edu/2019/05/17/the-blue-ticket-discharge-a-color-that-has-stained-the-lives-of-wwii-era-veterans-for-over-75-years/

Coming Out Under Fire: The Story of Gay and Lesbian Service Members. https://www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/gay-and-lesbian-service-members

circa 1940s

“I threw my uniform in the San Francisco Bay but I kept my dog tags.”

This was my first introduction to World War II. This was my father, Thaddeus G Mosley, talking about his return from his service with the US Navy in the Solomon Islands. Apparently, you had to turn in your dog tags to qualify for veteran benefits. The fact that African American service people did not get the same benefits as whites is often reported, but the intergenerational and lasting impact of getting less than they deserved is not discussed enough. It led to lower wages, less wealth, and an inability to secure housing or attend college. If you could attend college and get a degree, you were less likely to get a job in keeping with the degree you just acquired. So the cycle of having less than you deserve continued, and still does to this very day.

This injustice was bad enough, but it was made worse if you were one of the 48,000 African American, women, or LGBTQIA+ service people who were given a Blue Discharge. This was a neither honorable or dishonorable discharge that was disproportionately leveled at Black service people and those who were thought to be homosexual. While African Americans made up around 6.5% of the army during World War II, 22% of the Blue Discharges were given to Black soldiers. While it was abolished in 1947, there were no automatic reviews to determine veteran benefits.

One such soldier is Nelson Henry, Jr. According to Temple University news, the alumni was a student at Lincoln University when he enlisted in the army in 1942. Due to an old injury and further physical strain during training, he did not pass the physical to go overseas and was discharged. He was given a Blue Discharge, named for the blue paper it was printed on. Those with that discharge, though technically not a dishonorable discharge, were “routinely denied veteran benefits.” This was the case of Mr Henry, who fought for years to get his benefits reinstated. It was not until 2019 that his discharge was upgraded to an honorable one. Mr Henry died in 2020 of complications caused by the coronavirus.

Outfit

Upcycled wool suiting material lined in synthetic blue fabric and black ribbon by Tereneh Idia

Chain and Triple V for victory charm made from upcycled chains from Center for Creative Reuse (PCCR) by Tereneh Idia

Vest from upcycled upholstery fabric from PCCR by Tereneh Idia

Tie from C3 hemp and organic cotton flag fabric by Tereneh Idia

Vintage men’s shirt from eBay

Artist Reflections

The New Pittsburgh Courier was instrumental in the “Double V for Victory” campaign, the goal of which was to defeat fascism in Europe and anti-Black racism in the United States. But how do you fight for a country who does not see you as a full citizen, a full human being?

There are documented cases of violence and even the death of Black service people returning to their home towns in America in uniform, only to be killed in that uniform. Some whites were so disturbed to see a Black man in military uniform. Imagine surviving Hitler only to be killed by your white neighbors?

For this project I added another “V,” that of ending discrimination and injustice of the LGBTQIA+ community. Often in my social justice work and writing I say, “It is never one thing.” To allow injustice to one member of our human family impacts all of us.

References

A WWII veteran’s fight to receive an honorable discharge.

https://news.temple.edu/news/2020-11-09/wwii-veteran-s-fight-receive-honorable-discharge

Nelson Henry Jr., World War II vet who fought racism in Army, dies at 96.

https://www.inquirer.com/obituaries/pa-nelson-henry-veteran-army-blue-discharge-discrimination-appeal-philadelphia-20200511.html

“Blue” Ticket

https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/blue-and-other-than-honorable-discharges.htm#:~:text=During WWII, to cut costs,African Americans, and LGBTQ servicemen.

The Blue Ticket Discharge: A Color that has Stained the Lives of WWII-Era Veterans for Over 75 Years

https://mvets.law.gmu.edu/2019/05/17/the-blue-ticket-discharge-a-color-that-has-stained-the-lives-of-wwii-era-veterans-for-over-75-years/

Coming Out Under Fire: The Story of Gay and Lesbian Service Members. https://www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/gay-and-lesbian-service-members

Black Arts Movement

circa 1970s

“Elsie Neal owns and operates the Neighborhood Craft Shop,” is the introduction to a character on Mister Rogers Neighborhood as well as a Pittsburgh-based Black artist in real life. What we may overlook now as no big deal, upon reflection is quite revolutionary.